The Engineering of the Ultimate Prank Why “Medical-Grade” Realism is the New Standard for Viral Content

By Mark Allen, Special Effects & Prop Specialist

Back in 2010, you could film a prank video with a potato-quality camera, use a plastic water bottle taped to your leg, and get a million views. The audience didn’t care about the details; they just wanted the laugh.

Those days are dead.

In the age of 4K (and now 8K) streaming, the audience is ruthless. They can spot a fake from a mile away. High-definition cameras pick up everything—seams in silicone, unnatural skin tones, and liquid that looks too much like apple juice and not enough like biological reality. For the modern content creator, realism isn’t just an aesthetic choice; it’s a retention metric.

If your prop looks fake, the immersion breaks. If the immersion breaks, they click off.

This shift has birthed a strange but fascinating sub-market in the creator economy: the demand for “medical-grade” practical effects. And sitting unexpectedly at the top of this engineering hierarchy is a device most people misunderstand completely: The Whizzinator.

Let’s strip away the tabloid noise and look at this from an engineering perspective. Why are top-tier pranksters and practical effects artists turning to “biomimetic” devices instead of cheap gags?

The “Uncanny Valley” of Prank Props

We all know the concept of the “Uncanny Valley” in robotics—when something looks almost human but not quite, it becomes creepy. In high-resolution video, we have a similar problem with props.

I remember working on a set a few years ago where a director wanted a “bathroom humor” scene. The prop department brought in a cheap, novelty device they bought at a party store. Under the studio lights, it looked ridiculous. It was shiny, rigid plastic. It reflected light like a toy.

I worked on a prank shoot last year where the production used yellow-dyed water for a “plumbing accident” gag. Under the 4K studio lights, the liquid lacked the right viscosity and sparkled like apple juice. The comments section immediately roasted us, calling it “Gatorade” and destroying the immersion instantly.

To fool a 4K sensor, a prop needs to mimic three specific properties of human biology:

- Subsurface Scattering: Real skin absorbs light; plastic reflects it.

- Thermal Consistency: Heat affects how materials move and settle.

- Fluid Viscosity: Biological fluids don’t splash like water; they have a specific “weight.”

This is where the engineering of high-end fake urine kits crosses the line from “gag gift” to “cinema-grade prop.”

Biomimicry: The Tech Behind the “Whizzinator”

When you break down the specs of a Whizzinator Touch kit, you aren’t looking at a toy. You are looking at a simplified life-support system.

1. The Silicone Prosthetic (The Visual)

The core unit uses medical-grade silicone. Unlike latex, which degrades and discolors, silicone maintains “flesh-like” elasticity. In the FX world, we call this a “Hero Prop”—a prop designed to be filmed in extreme close-up. The molding process eliminates seams, which is usually the first giveaway in amateur content.

2. The Thermal System (The Tactile)

Here is where the engineering gets impressive. A bag of liquid at room temperature (70°F) behaves differently than a liquid at body temperature (98.6°F). Viscosity changes with heat. The Whizzinator utilizes organic heat pads designed to maintain a precise thermal window for up to 8 hours. In a filming scenario, this is critical. You can’t have your “actor” fumbling with a microwave between takes. The prop needs to be “body-ready” for the entire shoot duration.

3. The Fluid Dynamics (The Action)

Synthetic urine isn’t just yellow water. To look real on camera, the liquid needs the correct Specific Gravity (density relative to water) and pH balance. Why does this matter for a video? Because of how the liquid hits the surface. Water splashes chaotically. A liquid with the correct specific gravity (usually around 1.005 to 1.030) flows with a slightly heavier, more consistent stream. It captures light differently. It bubbles differently.

It sounds obsessive, but these are the details that separate a viral hit from a “cringe” compilation.

Why Creators Are Paying for “Medical-Grade”

If you are just pranking your buddy at a sleepover, a water balloon is fine. But the stakes for content creators are higher today.

We are seeing a trend called “Hyper-Reality” in content. Channels that focus on social experiments or high-stakes pranks are operating with budgets that rival indie films. They can’t afford a “bad take” because a prop malfunctioned or looked fake.

A device like the Whizzinator offers consistency.

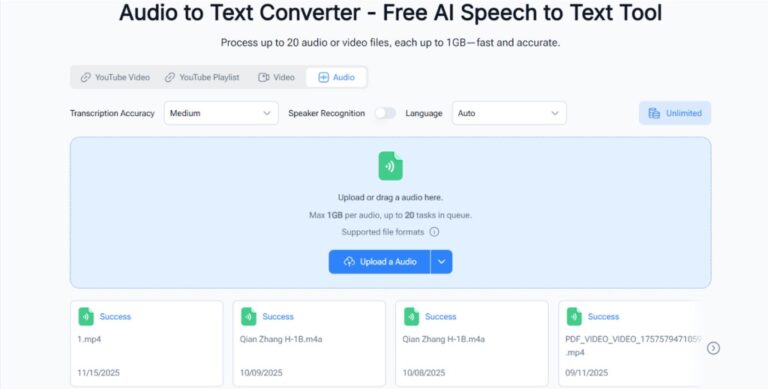

- Reliability: The valve systems are designed for one-handed, silent operation. No clicking sounds to ruin the audio.

- Repeatability: The “dried urine” refills allow for multiple takes without needing to reset the entire rig.

It is the same reason Hollywood uses squibs for gunshot wounds instead of ketchup packets. You pay for the engineering because you need the shot to work the first time.

The Verdict

We need to stop looking at synthetic urine kits through the narrow lens of “drug testing.” That’s a boring, limited conversation.

The reality is that we are living in a golden age of practical effects, accessible to anyone with a camera. Whether you are shooting a comedy sketch, a social experiment, or an indie film scene, the standard for realism has been raised.

If you want your audience to suspend their disbelief, you have to respect their intelligence. You can’t feed them plastic and expect them to buy it. You need engineering. You need biomimicry. You need the kind of realism that makes them question whether it was a prank at all.

And sometimes, that means buying the kit that was engineered to fool a scientist, just to fool your subscribers.